My Friend Kate Was No Cook

By Jennifer Cognard-Black

Originally appearing in Slackwater, Volume 7

My friend Kate was no cook—at least that’s what she would have had you believe.

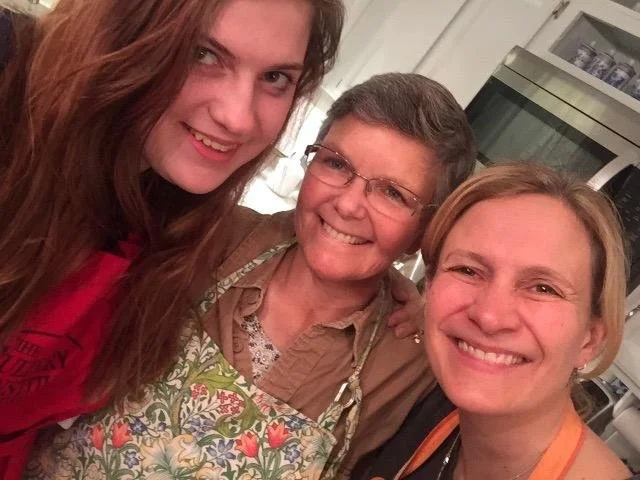

Kate Chandler and Kate Cognard-Black circa 2010

It’s true that Kate Chandler assembled her dishes more than cooked them. Among her friends and colleagues, we looked forward to potlucks or scrappy everyday meals that featured one or more of Kate’s assembled creations: a chocolate tofu pudding (made by pureeing); a seven-layer Mexican dip with chips (made by scooping and layering); a pimento cheese spread served with crackers (made by mixing); or, come March or April, breakfast-cereal Easter nests (made by folding corn flakes into microwaved chocolate and then shaping this mixture into “nests” topped with multi-colored jellybean “eggs”). These assembled dishes were easy and tasty, the kinds of food that Kate could pull together quickly from minimal ingredients and that she could make with children or teenagers, whom she often invited into her kitchen. Kate enjoyed getting sticky and smeary with chocolate-and cheese-covered kids, encouraging them to “sample” their creations along the way.

And so, if, as the Oxford English Dictionary says, the verb “cook” means “to prepare food by the action of heat” over a fire or a stovetop, it’s true that Kate rarely cooked. When she’d host her fellow English faculty for a holiday gathering, she’d put apple cider, orange slices, and cloves in a big pot on the stove— “mostly for the amazing smell,” she’d admit. For a Thanksgiving dinner for herself and her husband Rocky, she’d buy pre-roasted turkey slices, pre-whipped mashed potatoes, and pre-made gravy, which she’d pile on thick pieces of bread and put under her oven’s broiler. And she did have a crock-pot recipe from a friend at church for a healthy vegetable soup. To my knowledge, Kate made this soup maybe once a year—hacking up raw veggies and then pouring chicken broth over the pile, letting it simmer on low for the afternoon. After ladling out enough of this dinner for herself and Rocky, Kate would divide the rest into Tupperware containers, giving them out to the many local families she knew and nurtured.

So I will admit that my friend Kate was neither a gourmet nor a gourmand. She certainly wasn’t a chef, and she had only a passing resemblance to a cook if that’s a person who works with heat and fire. She was no archetypal maternal figure, spoon-wielding and apron-swaddled, urging people to “Eat, eat!” while sauces bubble merrily behind her. And yet, even though Kate wasn’t a traditional cook, she adored spending time with others around a welcoming table, sharing food—for food was at the center of her life. Indeed, hers was a life built around a generosity of spirit and a strong sense of community that food both invites and creates.

Over the many years of our friendship, apart from between-class hallway banter, I don’t remember having an interaction with Kate that didn’t involve food. If I popped by her office or if I brought my daughter Katharine by for a visit, Kate offered up something to eat. It might be a tub of Sabra hummus (the one with the pine nuts) and a bag of Stacy’s pita chips. It might be Triscuits (the cracked pepper variety) and hunks of cheddar cheese. Or it might be whatever crazy flavor of Oreos was new that season: strawberry milkshake, cool mint crème, banana split, brownie batter, pumpkin spice, peanut butter, key lime pie, blueberry pie, cinnamon bun, candy corn, ginger- bread, or red velvet. Kate Chandler and my daughter Katharine tried them all—and liked most.

I have to say that sharing these pre-packaged and quickly assembled foods with Kate was pretty much the best thing ever. She found such delight in the ingenuity of a cinnamon bun Oreo, such joy in building her Mexican dip, layer by layer— “like an archeological dig in reverse,” she once said. And yet the moments that still glow in my mind with a gilded light are the times that Kate and I got together to bake. My entire life, I’ve been a baker, and when I first became friends with Kate Chandler, I wanted to share my baking bliss with her—just as she shared her deep pleasure of pureeing, scooping, layering, mixing, melting, and folding with me.

During our baking sprees, Kate and I did, in fact, resemble archetypal bakers: we swung rolling pins and donned flour-dusted aprons. Our baking repertoire was simple but gloriously golden: cookies, cakes, quick breads, pies, and apple crisp. Over time, we developed baking rituals. For instance, we held “Pie Day” the day before Thanksgiving, and Kate, Katharine, and I would crank out between seven and ten pies—all with home- made crusts—for our loved ones to enjoy the following afternoon. We tried many distinct recipes for pumpkin and pecan pies—convincing ourselves that honey was the requisite ingredient in a pecan pie because we never failed to run out of Karo syrup and had to make do. And we came to worship my own mother’s self-created recipe for a double-crust apple pie, one with a layer of butter, sugar, cinnamon, and nutmeg snuggled up close be- neath the top crust.

We also ran our own test kitchens. One year, Kate and I tried out six different recipes for apple crisp—Rocky’s favorite—hunting tart, local apples from Amish and Mennonite stands and trying out lemon peel, crushed pecans, and peanut butter as intriguing add-ins. We performed similar tests with banana bread (turns out almond extract is spicier than vanilla) and chocolate-chip cookies (bacon bits add a rich flavor, while crushed potato chips disintegrate into mushy saltiness). And then there’s the recipe that became our most famous: the one for pumpkin-chocolate bread.

I say “famous” because it’s this pumpkin-chocolate bread that has been and still is the celebrated treat both Kate and I brought to our English students each semester, even when the weather wasn’t particularly autumnal. For more than a decade, we tried numerous incarnations of this recipe, ranging from one that called for cooked pumpkin scooped out of its hot, orange shell to another that insist- ed hand-chopped chocolate was superior to chips poured straight from a bag. Ultimately, Kate and I arrived at what is truly the perfect pumpkin-chocolate bread recipe. But even as generations of our students came to relish this indulgence and asked after the recipe, Kate and I kept our exact method and techniques a secret, just as an actual cook might.

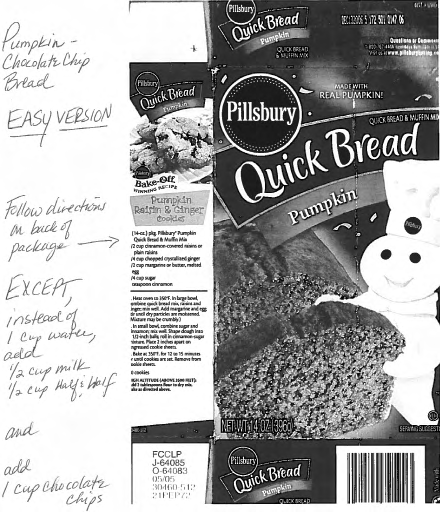

Now, though, with my friend Kate dead for over a year, I am ready to reveal our secret— which also reveals a cooking cheat. For here’s the thing: the best version of the pumpkin-chocolate bread recipe is also the easiest. It comes from a box mix, although the choice of the mix does matter.

I feel I must be honest: in our test-kitchen zeal—and in our willingness to assemble foods rather than cook them—Kate and I gave box baking a go. We sampled boxed banana bread, boxed chocolate-chip cookies, and (yes) boxed pumpkin bread. Of all of the labor-intensive and surprisingly easy pumpkin-chocolate bread recipes we put to the test, the most perfect bits of pumpkiny, spicy, chocolatey goodness came from the Pillsbury company, Doughboy and all.

Now, it’s vital that you use olive oil instead of vegetable oil, and you really must replace the necessary water with either milk or half-and-half. And then you are also required to add a half package of Nestlé Toll House chocolate chips. But other than these minor substitutions and additions and a couple of whisked-together eggs, it’s just mix, pour, bake, share, and eat.

It’s humble. It’s straightforward. And it’s also profoundly delightful. Much like my friend Kate.

So perhaps I, too, am no cook. I know I’m not fully legitimate when it comes to baking; I am yeast-shy and, with the exception of pie dough, I don’t mind using processed or pre-made ingredients. And yet I’m also no longer sure that to be a cook necessarily means that one must be fussy or complicated or fervently authentic. Let me return to the Oxford English Dictionary for a moment and pull out yet another definition of the word “cook.” In this case, it’s not the verb but the noun, which is applied to a woman, especially one who “manages the cooking within a family or a group”— such as in the phrase “a good, plain cook.”

In this sense, I would say that my friend Kate was definitely a cook. She cooked up ideas and plans; she cooked together friendships. She was a woman who “man-aged” both a literal and a figurative family around food. In feeding us, Kate reminded those she cared about just how connected we all are; she “assembled” and “layered” and “mixed” a community, one that brought together her many worlds: those of the classroom, church, and neighborhood and also those of her colleagues, family, and friends. Akin to the communion and intimacy of a slice of pumpkin-chocolate bread just out of the oven, Kate’s warm and beautiful being nourished and nurtured me—as well as the lives of many, many others.

Although Kate herself cannot be revived in body, I believe that our own bodies, memories, and hearts continue to carry her. And so in a spirit of sharing, caring, and carrying, I offer you the famous Kate Chandler pumpkin-chocolate bread to enjoy in remembrance of her: a late bread recipe—which you may assemble yourself and then give and enjoy in remembrance of her: a good plain cook.