Taking A Shot

By Jack Gelrud as interviewed by Marc Kriss on March 11 and April 8, 1998

Originally appearing in Slackwater, Volume 2

Born in Norfolk, Virginia, Jack Gelrud moved to St. Mary’s County in October 1948 after his discharge from the Army, in which he had served as combat medic in Italy. He opened up one of the first drug stores in Lexington Park. Gelrud attributes his decision to come to St. Mary’s County to the rural atmosphere of the 1940s. Over the years he has stayed close to his fellow servicemen. Many of his close friends, like Jack Daugherty and Robert Gabrelcik, were once pilots and share similar war experiences. In Gelrud’s eyes, these are the persons who have invested enormous amounts of time and money in the county’s growth.

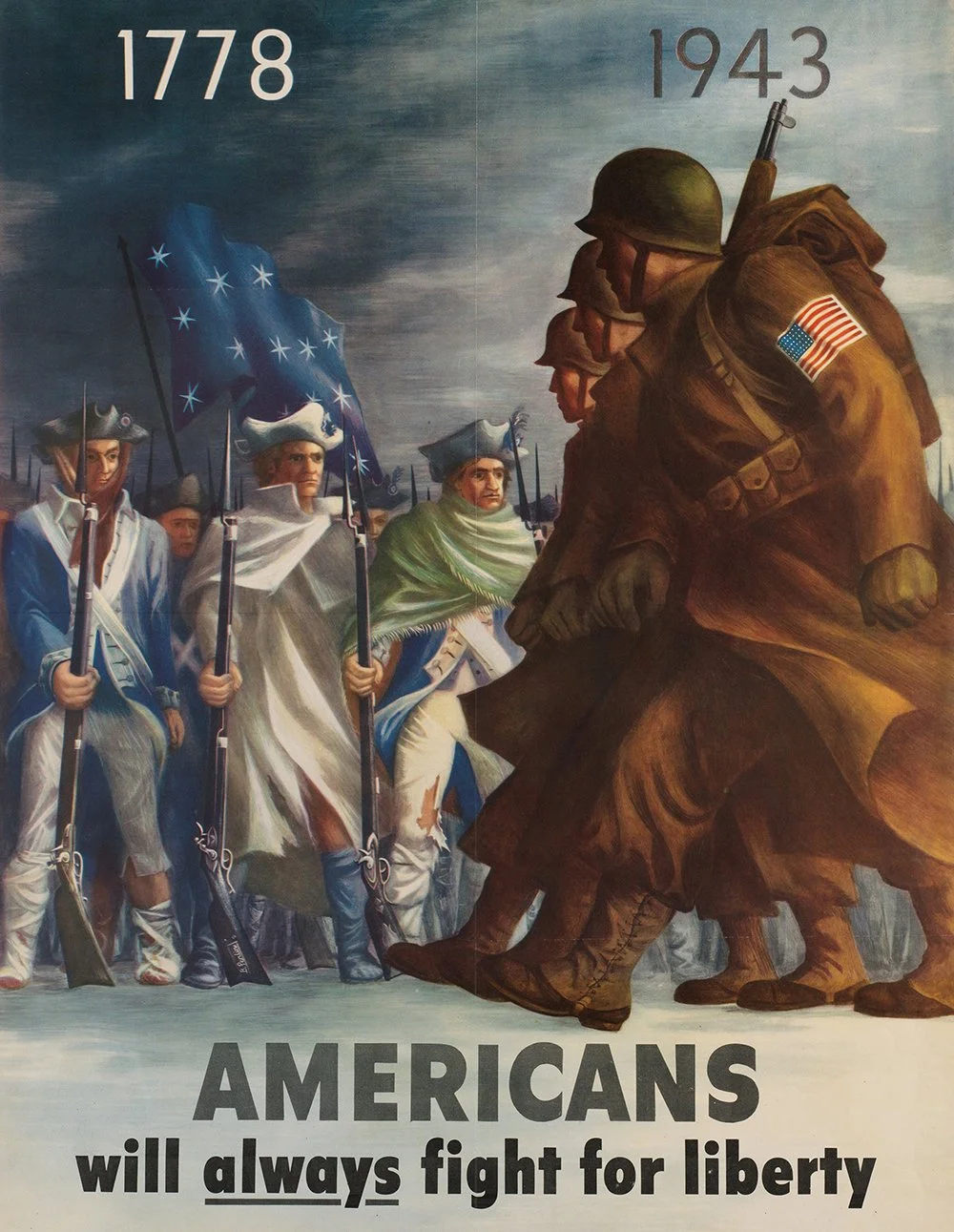

I was in college in 1942, and most of the boys who were in college at the time had a little bit of a guilt complex in some respect because they were in school and a lot of their contemporaries were being drafted. And as I said to you before, it was not an unpopular war as far as the young people were concerned, like Vietnam was, because everybody thought it was their patriotic duty to participate and help rid the world of Hitlerism and fascism and things like that. I’m sure there was a tremendous amount of propaganda which helped stir the pot, and it sort of blew the flames of patriotism a wee bit, so everybody said, “I’ve got to get in this and I’ve got to help.” A lot of my friends enlisted right after Pearl Harbor, and in fact I lost a few of the guys I participated in high school athletics with that went in very, very early. A lot of us enlisted the Naval Reserve when we were sophomores at colleges, with the Navy’s promise we would be able to graduate. When we finished school, we tried to get back to this naval program, which we thought was a pretty good program, but the Navy said, “Sorry, the program’s closed.” So we went into the general draft and were drafted into the service.

Photo by Boston Public Library on Unsplash

I have never had a problem adapting to where I am, even if I had no control over it. When you get drafted, you have no control over it. Now you can moan and gripe and say, “I don’t belong here,” and make yourself miserable. I was married at the time; it wasn’t the happiest thing in my life to go into the service, but I decided when I went in that if I moaned and griped about it, I would be miserable the whole time I was in. So I decided I was going to make the best of it. I got sent down to Camp Swift, Texas, right outside Abilene, for basic training.

Now one of the nice stories is that when I went down there, I traveled from Maryland to Texas by myself, which is unusual, but nobody else was assigned there. So I was given my own papers, my own food money, and I traveled that way. I went from Maryland to St. Louis, and from St. Louis by slow freight to Texas, and I think I stopped in every town going down. When I got down to Texas on a Sunday—and I don’t mind telling you, it was a lonely thing to walk into a camp on Sunday and not know anybody, even though I was a pretty up kid—it was a weird feeling. Here I was, carrying a duffel bag, and I didn’t know anything about the service except, “Here I am.” As a kid you don’t think with the same mind that you do as an adult. Although you think you’re an adult, you really aren’t. Your emotions carry you a lot further than your head does. So we all wanted to be in it, and after we were in it, we were wondering what the hell we were doing there—you know, “What did I do?”

A lot of the training we got in the service was actually in combat zones. My outfit came in at Naples, and from Naples we went to an area called Leghorn, which is right near Pisa. And we did outpost duty there, and from there we moved inland towards the Apennines and fought in a place called Riva Ridge and Monte Belvedere, which were two key battles in Italy. And we spearheaded the drive across the Po Valley and into the Alps.

As a combat medic you had to go out. If somebody got hit, it was your job to see that they were bandaged up, or given morphine if they were in pain, and evacuated from that area. Now on a couple of occasions, somebody would be caught out in the middle, and it would be a medic’s job to go out there and take care of him. So now you’re going to go out and wonder if anybody was going to pick you off while you were out there. But the two cases that I’ve experienced like that—and here again, don’t let anyone tell you that they’re not afraid—nobody fired, and we got the guy out. But your job as combat medic is to take care of people in the combat area when they get hit, and a lot of times you’re exposed. And a lot of times, in a bad situation, the lowest-ranking combat medic is the highest-ranking person on that field as far as evacuating people is concerned.

The only thing we had back then were the sulfa drugs, and penicillin just became available. And there were a lot of things you did that a doctor should have done, but you did them in the hope it would save somebody’s life. I’m a pharmacist, not a doctor. We did an emergency tracheotomy, which I wouldn’t want to do under any circumstance, but we did it, two of us, with a guy that was hit and couldn’t breathe. We did bandaging jobs for people that had lung punctures and things like that, and we were taught to do that. In fact, before we went into combat, we would use certain clothing the person had with them, such as a raincoat or a rain jacket, over the bandage to form an air-tight seal. There’s a lot of things we did that would be punishable if you did it as a civilian, but in the combat area, you do what you hope will save a person’s life.

So we spearheaded the drive across the Po Valley all the way up to areas like Montecatini and Lake Garda, and up towards the Austrian Alps. And that’s where the war ended for us in Italy. In a way, we were very fortunate to be pulled back and reorganized and put aboard ships and shipped back to the states. Our assignment was to stop in the states, regroup, and we were going to be shipped to the Pacific, because the Japanese had not surrendered at the time that we left Rome. Our assignment was to hit the northern islands of the Japanese chain, which were cliffs, and they wanted mountain troops. From what we saw, it was actually a suicide mission. But halfway home they bombed Nagasaki and Hiroshima, and the war was over, and then we were assigned to our camps and were told that if we had enough points we could be discharged.